From Danzón to Duke Ellington: Jazz’s Mexican Journey

Jazz, which emerged in the United States at the end of the 19th century, soon found fertile ground in Mexico for its reception and transformation. Early contact between Mexican and American musicians allowed the genre to spread throughout the country, where it acquired its own characteristics through interaction with local traditions. Over more than a century, jazz in Mexico has gone through phases of introduction, consolidation, experimentation, and contemporary revitalization, becoming an essential component of national cultural life.

The roots of jazz in Mexico go back to the 1880s, when Mexican military bands performed in New Orleans and some of their members stayed behind, participating in the development of the earliest jazz expressions. Later, during the first decades of the 20th century, Prohibition in the United States encouraged the arrival of foreign musicians to Mexico, who found a welcoming environment in the dance halls and theaters of Mexico City.

By the 1930s, large jazz orchestras had become part of the Mexican musical landscape, integrating into urban entertainment circuits. This process reached a milestone in 1954 with the production of the first national jazz recording. Likewise, the presence in Mexico of international figures such as Duke Ellington, who performed at the Palacio de Bellas Artes in 1968, underscored the cultural relevance that jazz had acquired in the country.

During the 1950s and 1960s, a period known as the “golden age” of jazz in Mexico took shape. This era was marked by the proliferation of specialized clubs, the emergence of new audiences, and the shift from big bands to smaller ensembles, which allowed greater space for improvisation. At the same time, the genre began to engage in dialogue with local musical expressions, opening fertile ground for sonic experimentation.

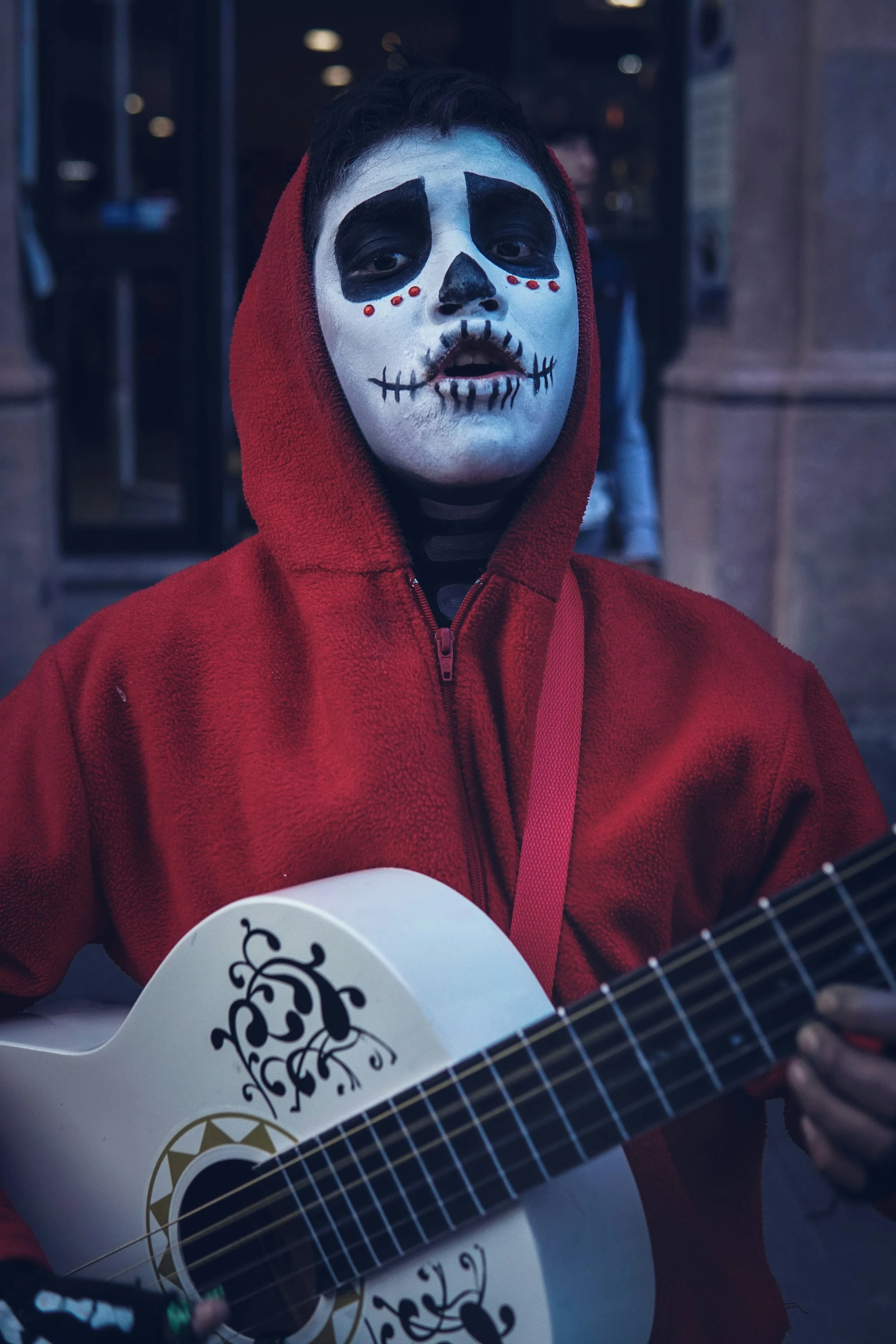

The interaction of jazz with traditions such as danzón, mambo, and later son jarocho, among others, led to musical proposals that went beyond merely imitating foreign models and instead encouraged fusion. In this way, jazz in Mexico became a space of cultural synthesis, where Afro-Caribbean and national influences converged, generating a distinctive style within the Latin American scene.

On the other hand, it’s important to note that Mexican music has found in jazz a fertile ground for reinvention. Songs like “Bésame mucho” by Consuelo Velázquez have become international standards, reinterpreted by jazz musicians who see in its lyricism a space for improvisation. Another iconic example is “Frenesí” by Alberto Domínguez, which Artie Shaw brought into the realm of swing in the 1940s, marking a milestone in the global projection of Mexican song. Even popular melodies like “La Llorona” and “Cielito Lindo” have been the subject of jazz arrangements, where traditional forms dialogue with modern harmony and interpretive freedom. In each adaptation, the Mexican essence is transformed without being lost, showing that these songs have a universal character capable of resonating in the language of jazz.

According to writer Ruy Castro, the foremost chronicler of Bossa Nova, this was not a genre created to sell millions, but to change aesthetics. It was a revolution of subtlety. In fact, its impact on jToday, Mexican jazz culture is expressed both in clubs in Mexico City and in a national network of festivals. Venues like Zinco Jazz Club and Parker & Lenox, along with events like the Riviera Maya Jazz Festival and the Nuevo León Jazz Festival, position the country as a regional reference. Likewise, the inclusion of jazz in educational institutions has strengthened the training of new generations, ensuring the genre’s continuity and renewal both nationally and internationally.

The historical journey of jazz in Mexico reflects a process of cultural appropriation that goes beyond merely receiving a foreign genre. From its earliest encounters in the 19th century to its current consolidation in festivals and academic spaces, jazz has helped enrich the cultural life of the country while developing its own style in dialogue with the global tradition of the genre.

by José Daniel Mejía Valle